A Review of Stability in the Niger Delta

Background

August 2022 has seen a number of events in the Niger Delta that threaten to destabilise the region again. The key drivers of instability remain centred around the exploitation of the region’s primary source of revenue – its hydrocarbon resources. The exploitation of these resources permeates almost every facet of the socio-political character of the region, with contracts for service companies and security suppliers becoming hotly contested sources of tension between communities, companies and political actors at the Local Government Area (LGA) and State levels.

This nexus of commercial interests and drivers of instability has been the enduring feature of the region since the 2009 Presidential Amnesty Program was introduced to end the militancy in the region. In August 2022 we saw the issues re-emerge and resulting in the possibility of increased inter-communal conflict.

The region is not a simple monoculture when it comes to crime and violence. Cultism, ritualism and robbery are an enduring feature of life for the people of the region. Recent weeks have highlighted the levels of risk facing both indigenous people and visitors, the latter including people travelling to the region for work. However, this analysis will focus on how the competition for economic advantage arising from oil and gas contracts is a significant driver of instability.

Oil and Gas under Siege

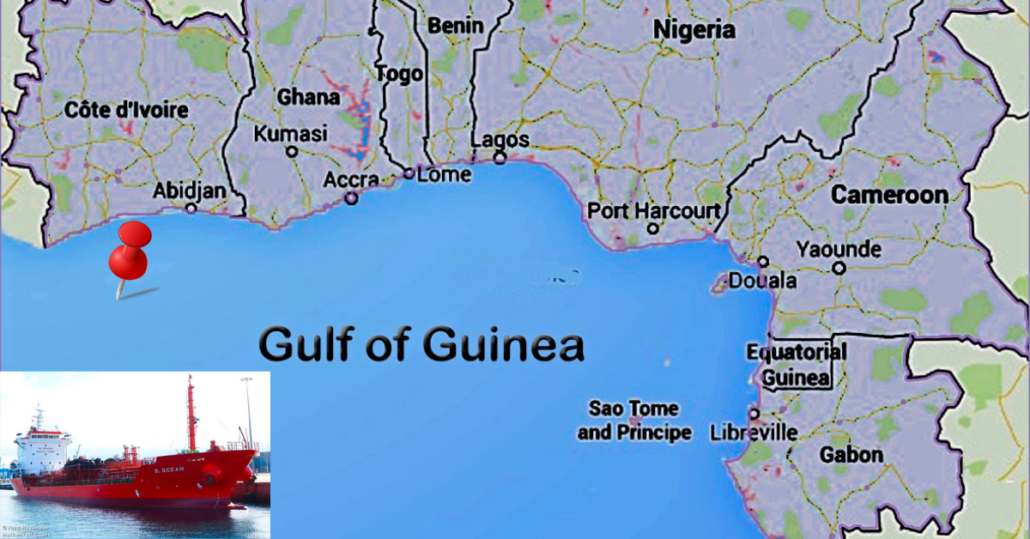

The surge in pipeline vandalism, illegal oil and condensate tapping and artisanal refining is contributing to huge environmental damage across the region, the loss of lives in fires and explosions at bunkering sites and illegal refineries, and an increase in competition between the gangs involved in the illegal industry of oil theft. Fires and explosions at illegal refineries have increased significantly in 2022, with major events occurring in the Ohaji-Egbema LGA, Imo State, in April 2022 and Ukwa West LGA, Abia State, in May and again on 21 August. In August, a tanker that was conveying illegal petroleum products exploded in Eleme LGA of Rivers State. These incidents all resulted in multiple deaths.

The environmental impact of the pipeline tapping, and illegal refining is massive. Many illegal refineries dispose of the residue from their unsophisticated refining techniques by simply pouring the tar-like reside into the nearest waterway.

The economic impact of the bunkering and artisanal refining is also huge. It was reported in July that 90% of oil that should be reaching the main terminal at Bonny is lost to crude oil thieves. One commentator said in August that,” If you pump 239,000 barrels of crude oil into either of the Trans-Niger Pipeline or the Nembe Creek Trunk Line they will receive 3,000 barrels. It got to a point where it was no longer economically sustainable to pump crude into the lines and a force majeure was declared”. Condensate lines are also heavily targeted as this by product of gas production requires almost no further refining and can simply be mixed with genuine petrol to provide income for the bunkering gangs and also the downstream fuel outlets that enjoy enhanced profit margins.

Illegal bunkering has also expanded dramatically in the last 12 months so much so that the Nigeria Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) recently reported that the nation’s oil output dropped by 12.5 per cent to 1.4 million barrels per day, including condensate, in the first half of 2022, down from 1.6 mbpd in the corresponding period of 2021. One media source also reported that bunkering cartels stole between 200,000 and 400,000 barrels of crude daily during the period.

Powerful Forces Threaten Stability

The biggest threat to stability in the region at present is the competition between the powerful cartels behind the bunkering. In this context, Bayelsa State has witnessed a spate of oil and gas related targeted killings in recent weeks.

On 12 June, the former MEND militant leader known as Commander Ebi Albert was shot dead in a targeted killing in the Biogbolo suburb of Yenagoa. He was one of the first tranche of militants to embrace the amnesty. His killing was the latest in a series of targeted assassinations of former militant leaders in the state.

Also in June, gunmen killed Francis Kolubo, the paramount ruler of Kalaba community in Yenagoa LGA, together with the chairman of the Community Development Committee (CDC), Samuel Oburo. The murders reportedly were the result of fierce opposition by the two victims to the establishment of a crude oil bunkering camp on the outskirts of the community. They believed that such a development would hinder the further development of the community by the Nigerian AGIP Oil Company. The pushback against their plan by the community leaders triggered a spate of attacks on NAOC pipelines by the bunkering gang, who subsequently secured a pipeline surveillance contract from NAOC.

In early July, also in Yenagoa LGA, gunmen in military fatigue shot dead a former militant leader, Indukapo Ogede at a hotel at Okutukutu. He was the Coordinator of Operations for Darlon Oil and Gas Servicing, an indigenous pipeline surveillance company.

As the 2023 elections loom over the horizon, the Federal Government has realised that this illicit parallel industry is a strategic and potentially existential threat to the nation. The oil and gas sector generates the vast majority of the country’s foreign currency earnings, and the strategic losses being suffered on lines such as the Trans-Niger Pipeline (TNP) that feeds Bonny Terminal have now reached a level of criticality that can no longer be ignored.

As the country faces a crippling shortage of foreign currency reserves – witness the recent crisis over repatriation of profits by foreign airlines resulting from government measures to protect its reserves – the Federal Government has decided to attack the problem at its roots – in the Niger Delta. However, the question of whether this chosen strategy will help or drive further instability in the region remains unanswered.

The Government Acts – But is the Solution Likely to Work?

The recent award of a massive pipeline surveillance contract to the former MEND leader Government Ekpemepulo, AKA Tompolo, has generated significant tension in the region, as many other powerful influencers and former militants feel that the award disenfranchises them. Indeed, the tension has extended beyond the region, resulting in a challenge by the Amalgamated Arewa Youth Groups (AAYG), a northern entity. This challenge itself has been rejected by the Ijaw youths from the six states of Niger Delta who have publicly stated that the contract, worth more than N4 billion per month, will actually help reduce crude oil theft in the region. Former MEND militant leaders also pointed out that the AAYG, a coalition of approximately 225 northern youth groups, should focus more on the problems in the north of the country.

AAYG protesters also stormed the NNPC headquarters in Abuja calling for the revocation of the contract and the resignation of the Oil Minister, Timipre Silva – a former governor of Bayelsa State with alleged links to MEND leaders in the state.

The Ijaw Youth Council Worldwide (IYC), countered that Tompolo would help save the country billions of naira being lost through oil theft and pipeline vandalism. The former MEND commander, Oyimi 1, who is also Chairman of the Movement for the Actualisation of the Dreams of Niger Deltans (MADND), said Tompolo would not be distracted by the AAYG comments.

However, on 05 September, the coordinator of the group, Muktar Adamu, announced the group had dropped its objection to the contract award, saying “the award of the contract was transparent and well-advertised, and followed due process”. The apparent reason was that they had seen that the contract had not been awarded to Tompolo directly, but to a company in which he has an interest.

While Tompolo’s two companies had contracts covering part of Bayelsa, Delta, Ondo Imo and Rivers States, three other companies were awarded the other contracts.

Former militants and community leaders in both Bayelsa and Rivers issued statements criticising the award of a region-wide contract to a single contractor, claiming they should also have benefited from the opportunities arising from the contracts.

A former militant leader in Bayelsa who identifies himself as General Lamptey, said there was no way Tompolo’s companies would be allowed to work in those areas of the state where local leaders that should have benefitted. He further stated that people on the ground would resist the surveillance contractors of Tompolo’s companies.

In Rivers State, militant leaders in the Kalabari areas, which they claim hosts 83 kilometres of pipelines (referring to the Nembe- Creek Trunk Line (NCTL)), stated that ignoring Ateke Tom and Dokubo Asari would lead to a situation where the surveillance contractors would not be able to work in Rivers State.

In the north-west of the region, community leaders in Delta State called on the Federal Government to award a separate contract to a company owned by an Urhobo indigene where pipelines transit areas populated by Urhobo communities. Similarly, in Edo State, speaking on behalf of the oil producing communities and stakeholders in the State, Chief Dr Patrick Osagie Eholor called on the Federal Government and Tompolo to engage in a dialogue and “carry those people along”, stating that they have competent people in the OML30 licence block who can take care of the Trans-Forcados Pipeline (TFP) in that area.

Responding, in an interview in early September, Tompolo explained that he would be engaging with major militant leaders in Rivers State – including Dokubo Asari and Ateke Tom – and they would realise the way ahead. He made it clear that all the major players would be included in the overall delivery of the contract, with plans to meet key players in Ondo, Imo and Rivers States. The former leader of the IYC, Chris Ekiyor, explained that the people protesting against the contract were simply impatient and need to engage with Tompolo to understand how the contract would be delivered.

The Ijaw National Congress (INC), the overarching body of all Ijaws, set up a committee to reduce tension arising from the pipeline surveillance contract.

Nevertheless, on 11 September, media reported that Asari threatened to confront and disarm any personnel working on the Tompolo contract who enter the Kalabari lands in Rivers State.

Can the Challenge Be Met?

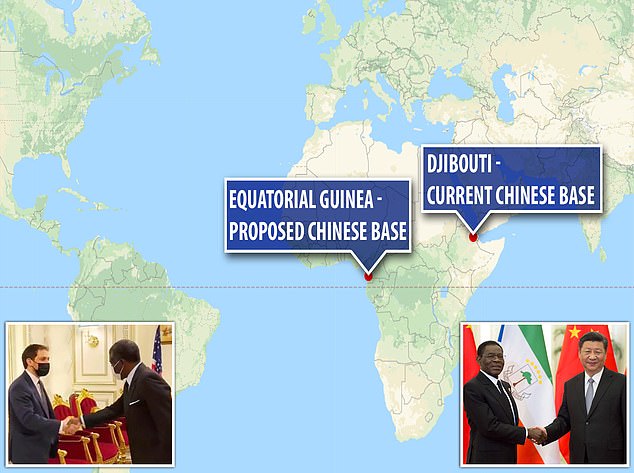

In late August, the Senior Special Assistant to President Muhammadu Buhari on Media and Publicity, Mallam Garba Shehu, said the federal government would soon go public with the identity of highly-placed Nigerians behind oil theft in the country. He implied that the ‘big men’ behind the industrialised theft of the nation’s wealth included members of the political elite and the security organs. His assertion that the cartel includes senior people in the armed forces was an echo of a 2019 statement by Rivers State Governor, Nyesom Wike. He claimed that the cost of such operations was beyond the reach of low-level community based criminal gangs. Illustrating his point is the case of the MV. Heroic Idun, a 3 million barrel capacity very large crude carrier, which allegedly managed to lift 3 million barrels of crude illegally while in Nigeria waters. Its subsequent escape to Equatorial Guinea remains contentious and largely unexplained.

Sheu’s words might herald a forthcoming clash between Tompolo’s contractors and powerful actors who will use the security forces to protect their operations. More likely is a pragmatic balance being reached and the oil theft continuing after a suitable interval in which the contract will be hailed as a success. The contract award can be viewed as an extension of ‘Operation Dakatar Da Bararrwo’, which was launched on 01 April. Since its launch, 23,110,102.59 litres of diesel have been seized while crude oil was put at 39,664,420.16 litres or 230,882.73 barrels. For kerosene, about 649,775.38 litres were confiscated; while PMS had recovery of 345,000.49 litres, Sludge 380,000 litres, and LPFO 66,000 litres. During the operation, 85 suspects were arrested with 72 Boats while 23 vehicles were also seized. At first glance, these figures are impressive. However, they represent a mere skimming of the surface and the arrest and disruption of the very lowest levels of the illicit activity. The major cartels that steal on an industrial scale will remain untroubled by such operations.

Militants and Surveillance Contracts

Sylva and Kyari decided to award the contract to Tompolo based on his history of leading the highly franchised militant groups in the first decade of the century and his handling of a pipeline surveillance contract in Delta State in 2014-15 with Oil Facilities Surveillance Limited. Some senior military leaders as well as some governors in the region pushed against the award.

Awarding pipeline surveillance contracts to former militant leaders is not unprecedented. In 2014, a contract was awarded to Oil Facilities Surveillance Limited, which was owned by APC chieftain, Chief Emami Ayiri and the PDP’s Chief Michael Diden, AKA Ejele, to secure pipelines in Delta State. Other contracts were awarded in Bayelsa to ‘Macaiver’ and in Rivers State to Farah Dagogo and Dokubo Asari under the overall control of Ateke Tom. The contracts ended in 2015 ahead of the forthcoming elections. Since then, a patchwork of contracts has been awarded to various companies.

The government perception is that of all the contractors awarded lucrative contracts, only Tompolo has succeeded in securing pipelines.

Can Tompolo Succeed?

It is reported that he has reached an understanding with the commander of the JTF that it will work collaboratively with his companies. Tompolo is also perceived by the government as someone who knows the terrain, who understands the bunkering business and who commands a substantial number of men who will aggressively attack the problem of policing the pipeline networks.

Tompolo has mounted a significant and successful diplomatic campaign to win over his detractors in the region and beyond. Indeed, in the first week of September, the AAYG reached an understanding with Tompolo and the leader of the Itsekiri youth movement (the Itsekiri Leaders of Thought), who met with Tompolo on 11 September to work out a protocol whereby the Itsekiri and Ijaw can both benefit from the contract. The following day, the Itsekiri leaders began recruitment for the contract indicating a satisfactory outcome to the meeting.

At his headquarters in Oporoza in the Burutu Kingdom of Delta State, he has also held meetings with a succession of former militants, community leaders, journalists, security forces commanders, bunkering gang leaders, and pressure groups. His efforts appear to be bearing fruit and the hope is that the status quo will be maintained in the region but only time will tell.